The only organisation that cannot see the methane threat is the much vaunted IPCC.

--Kevin

Hester

Methane

Seeps Out as Arctic Permafrost Starts to Resemble Swiss Cheese

Measurements

over Canada's Mackenzie River Basin suggest that thawing permafrost

is starting to free greenhouse gases long trapped in oil and gas

deposits.

19 July, 2017

Global warming may be unleashing new sources of heat-trapping methane from layers of oil and gas that have been buried deep beneath Arctic permafrost for millennia. As the Earth's frozen crust thaws, some of that gas appears to be finding new paths to the surface through permafrost that's starting to resemble Swiss cheese in some areas, scientists said.

In a study released today, the scientists used aerial sampling of the atmosphere to locate methane sources from permafrost along a 10,000 square-kilometer swath of the Mackenzie River Delta in northwestern Canada, an area known to have oil and gas desposits.

Deeply thawed pockets of permafrost, the research suggests, are releasing 17 percent of all the methane measured in the region, even though the emissions hotspots only make up 1 percent of the surface area, the scientists found.

In those areas, the peak concentrations of methane emissions were found to be 13 times higher than levels usually caused by bacterial decomposition—a well-known source of methane emissions from permafrost—which suggests the methane is likely also coming from geological sources, seeping up along faults and cracks in the permafrost, and from beneath lakes.

The findings suggest that global warming will "increase emissions of geologic methane that is currently still trapped under thick, continuous permafrost, as new emission pathways open due to thawing permafrost," the authors wrote in the journal Scientific Reports. Along with triggering bacterial decomposition in permafrost soils, global warming can also trigger stronger emissions of methane from fossil gas, contributing to the carbon-climate feedback loop, they concluded.

"This is another methane source that has not been included so much in the models," said the study's lead author, Katrin Kohnert, a climate scientist at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, Germany. "If, in other regions, the permafrost becomes discontinuous, more areas will contribute geologic methane," she said.

Similar Findings Near Permafrost Edges

The findings are based on two years of detailed aerial atmospheric sampling above the Mackenzie River Delta. It was one of the first studies to look for sources of deep methane across such a large region.

Previous site-specific studies in Alaska have looked at single sources of deep methane, including beneath lakes. A 2012 study made similar findings near the edge of permafrost areas and around melting glaciers.

Now, there is more evidence that "the loss of permafrost and glaciers opens conduits for the release of geologic methane to the atmosphere, constituting a newly identified, powerful feedback to climate warming," said the 2012 study's author, Katey Walter Anthony, a permafrost researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

"Together, these studies suggest that the geologic methane sources will likely increase in the future as permafrost warms and becomes more permeable," she said.

"I think another critical thing to point out is that you do not have to completely thaw thick permafrost to increase these geologic methane emissions," she said. "It is enough to warm permafrost and accelerate its thaw. Permafrost that starts to look like Swiss cheese would be the type that could allow substantially more geologic methane to escape in the future."

Róisín Commane, a Harvard University climate researcher, who was not involved with the study but is familiar with Kohnert's work, said, "The fluxes they saw are much larger than any biogenic flux ... so I think a different source, such as a geologic source of methane, is a reasonable interpretation."

Commane said the study makes a reasonable assumption that the high emissions hotspots are from geologic sources, but that without more site-specific data, like isotope readings, it's not possible to extrapolate the findings across the Arctic, or to know for sure if the source is from subsurface oil and gas deposits.

"There doesn't seem to be any evidence of these geogenic sources at other locations in the Arctic, but it's something that should be considered in other studies," she said. There may be regions with pockets of underground oil and gas similar to the Mackenzie River Delta that haven't yet been mapped.

Speed of Methane Release Remains a Question

The Arctic is on pace to release a lot more greenhouse gases in the decades ahead. In Alaska alone, the U.S. Geological Survey recently estimated that 16-24 percent of the state's vast permafrost area would melt by 2100.

In February, another research team documented rapidly degrading permafrost across a 52,000-square-mile swath of the northwest Canadian Arctic.

What's not clear yet is whether the rapid climate warming in the Arctic will lead to a massive surge in releases of methane, a greenhouse gas that is about 28 times more powerful at trapping heat as carbon dioxide but does not persist as long in the atmosphere. Most recent studies suggest a more gradual increase in releases, but the new research adds a missing piece of the puzzle, according Ted Schuur, a permafrost researcher at Northern Arizona University.

Since the study only covered two years, it doesn't show long-term trends, but it makes a strong argument that there is significant methane escaping from trapped layers of oil and gas, Schuur said.

"As for current and future climate impact, what matters is the flux to the atmosphere and if it is changing ... if there is methane currently trapped by permafrost, we could imagine this source might increase as new conduits in permafrost appear," he said.

"NATO

and the United States should change their policy because the time

when they dictate their conditions to the world has passed,"

Ahmadinejad said in a speech in Dushanbe, capital of the Central

Asian republic of Tajikistan

‘Hotspots’

in the Arctic Permafrost Are Dumping Methane Into the Atmosphere

19

July, 2017

Methane-sniffing airplanes have mapped the release of a powerful greenhouse gas in Canada's Arctic.

Locked

away in the Arctic permafrost is what's frequently

called the

"ticking time bomb" of climate change—methane, a

greenhouse gas many

times more powerful than

carbon dioxide. There's widespread worry that, as the permafrost

thaws, large amounts of methane will spew into the Earth's

atmosphere, worsening the effects of climate change.

There's

reason to be concerned. The Arctic is

warming faster than

anywhere else on Earth, and the permafrost—which acts like a cap

over vast

amounts of methane,

preserved there for millions of years—is

thawing.

But scientists still don't know how much methane is leaking out and

how quickly, or whether it could realistically reach a "tipping

point."

Understanding all this is crucial, and new research gets us closer.

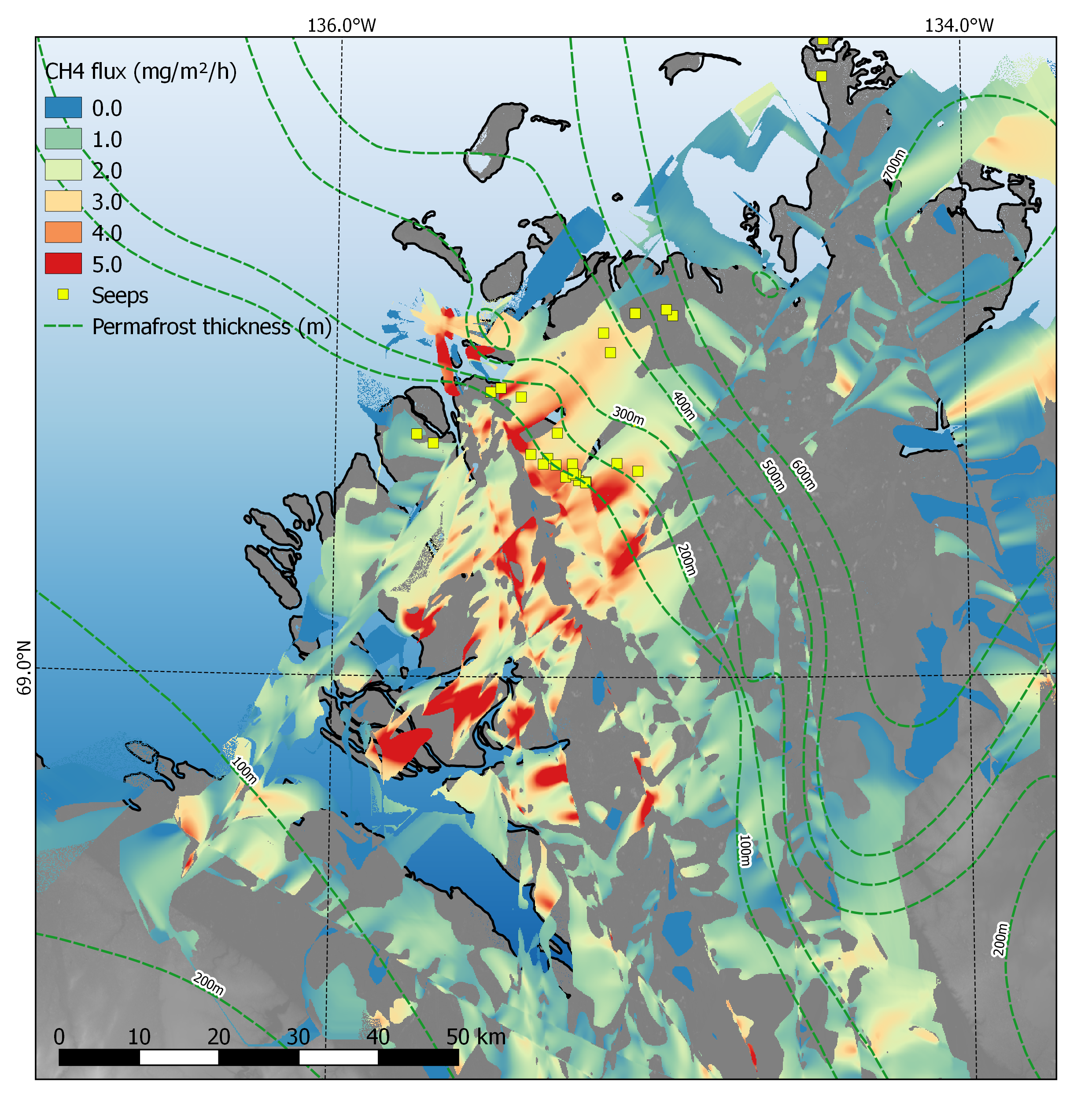

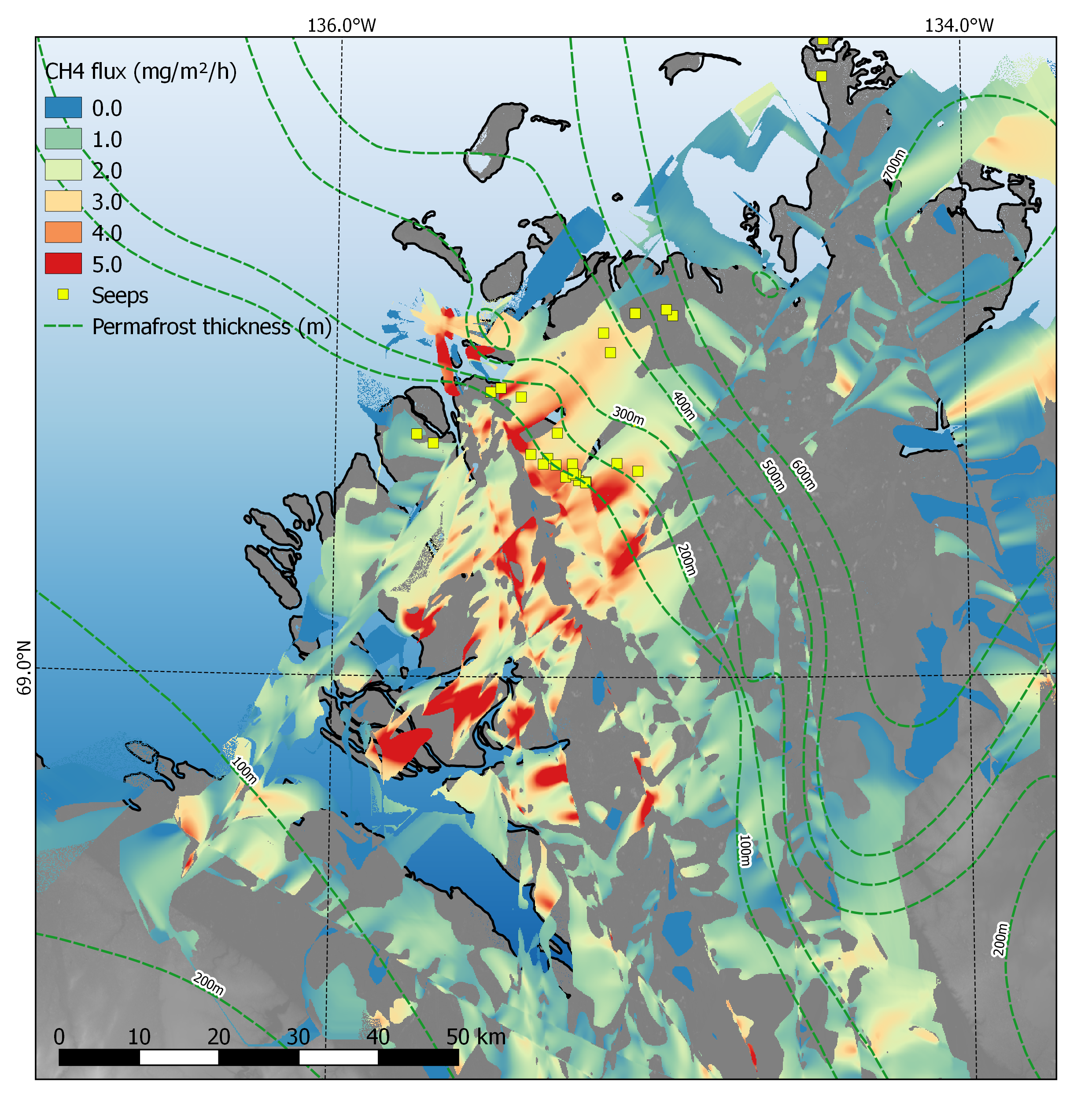

"

Map

of the methane fluxes in the northern study region. Image: B.

Juhls/GFZ

Scientists

have made a high-resolution map of methane emissions across the

Mackenzie Delta region in

Canada's Arctic. The area comprises "10,000 square kilometers,"

Katrin Kohnert of the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences told

me. Until now, most of the research we had on methane leaking from

the permafrost came from localized studies on the ground, explained

GFZ scientist Torsten Sachs. Sachs and Kohnert are authors on the

paper, published Wednesday in Scientific

Reports,

describing how their team used methane-sniffing airplanes to survey

the region and get a sense of what was happening.

"This

is the first study using this particular method with airplanes,"

Sachs told me. According to him, the plane is a modernized

and modified DC-3,

originally built in 1943.

Flying

about 50 meters above ground over the Arctic between July 2012 and

July 2013, the researchers had a bird's eye view.

"He's

flying a pretty large airplane extremely close to the ground. It's

pretty unique," Charles Koven, research scientist with the Earth

and Environmental Sciences Area at the Lawrence Berkeley National

Lab, told me in a phone call. Koven didn't participate in this paper,

and hadn't had a chance to read it before I spoke with him, but he is

familiar with Sachs' work. "Torsten has a tolerance for risk

that's above that of most people," Koven added.

A

view out the window of the research aircraft over the Mackenzie

Delta. Image: T. Sachs/GFZ

Permafrost

is unequally thick across the Mackenzie Delta, Sachs and Kohnert

explained in a phone call. In some places, it's relatively thin

(about 100 meters) and in other places it's up to half a kilometre

thick. Their team found that certain "hotspots"

representing only 1 percent of the region—places where it was

permeable, akin to cracks or holes in the cap—contributed 17

percent of the annual estimated methane emissions.

Methane

is being released from the permafrost in a couple of different ways.

As soil thaws, microbes munch away at its organic materials,

producing greenhouse gases. Less well understood is the release of

"geologic" methane contained in the massive oil and gas

deposits across the Arctic, and the latter is what has many people

concerned.

Thawing

permafrost will contribute not only to increased "biogenic"

methane (from microbes), but also "increased emissions of

geologic [methane]," the paper reads, "currently still

trapped under thick, continuous permafrost, as new emissions pathways

open."

Does

that mean we could reach a dramatic "tipping point" where

the permafrost is so degraded that methane dumps rapidly into the

atmosphere? Sachs compared it to punching holes in a jar's lid. "In

theory, you could imagine [tapping] big reservoirs underneath,"

he said. "But usually the thawing is gradual. I don't think it

will be catastrophic."

Koven

said that scientists need more observations of what's going on at

every scale—localized studies on the ground, alongside studies from

airplanes and space-based satellites—to understand the risks. There

are still so many unknowns.

"What

we do know, with some confidence, is that warming is going to lead to

a thawing of the permafrost, which will lead to a bunch of different

outcomes," he said. One will be the release of more greenhouse

gases, including methane. "Another thing we don't know nearly as

well," Koven continued, is whether we could hit some kind of a

tipping point. "The evidence for those is not as good, but we

can't rule them out completely."

Thawing

permafrost poses even greater global warming threat than previously

thought, suggests study

As

the world warms, methane trapped underneath the frozen tundra could

be released, increasing the rate of warming in a vicious circle

19

July, 2017

Runaway global warming is, without a doubt, a nightmare scenario for humanity.

As

the temperature rises, it has knock-on effects that drive the mercury

higher still in a vicious circle that the likes of Professor Stephen

Hawking have warned could turn the Earth into a planet like Venus,

where it’s a balmy 250 degrees Celsius and the rain is made of

sulphuric acid.

One

of the most feared of these feedback loops is the vast amount of

organic material currently trapped in permafrost, which would release

methane and other greenhouse gases in large amounts given the right

conditions.

And

now a team of researchers has discovered another significant source

of emissions that would result from the thawing of the tundra. For

the frozen ground acts as a cap on much more ancient gas deposits,

preventing them from escaping into the atmosphere.

These

seeps were known about, but just how important they would be was

poorly understood.

The

new study, of 10,000 square kilometres of the Mackenzie Delta in

Canada, found that the seeps there were responsible for 17 per cent

of the total emissions from the land even though they were only found

in about one per cent of the area, according to a paper in the

journal Scientific Reports.

One

of the researchers, Professor Torsten Sachs told The Independent: “We

were a bit surprised … we saw these very strong emissions. It means

a very tiny fraction of the area produces quite a big share of the

estimated annual emissions.

“And

that tells us maybe we should not just focus on biogenic methane

production in the upper lawyers of the permafrost, but pay a bit more

attention to this potential effect.

“If

we punch holes in the ‘lid’ [created by the permafrost], the

stuff underneath may find its way up.”

Professor

Sachs, of the German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, said

the area they studied had been “discontinuous” permafrost for a

long time and so probably had had such seeps well before humans began

to notice global warming.

But

the thawing of permafrost in places like the coastal plains of North

Alaska and the major river basins of Siberia could open up new

methane seeps.

By

studying the Mackenzie Delta, Professor Sachs said the researchers

had opened “a window into the future”.

How

big an effect this new source of methane would be was "speculative",

he added, adding that further study was needed to try to work this

out

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.